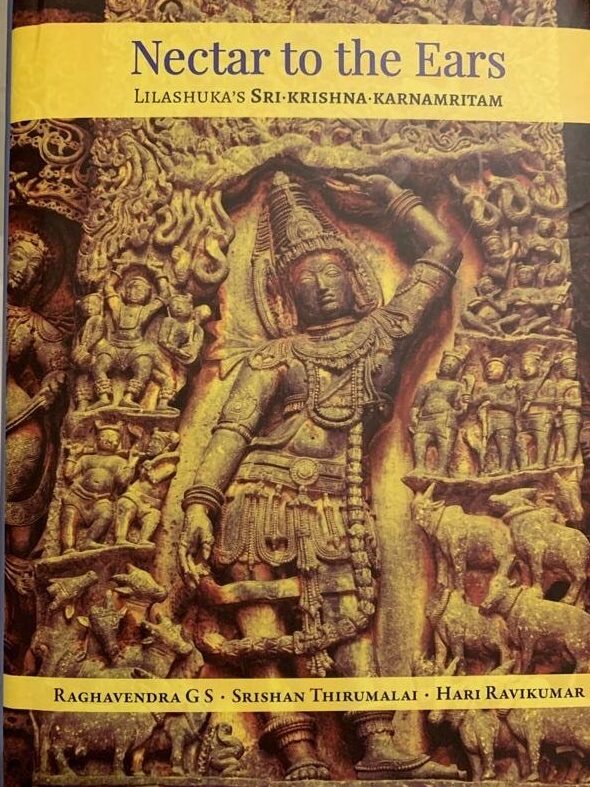

Nectar to the Ears

Lilashuka’s Sri-Krishna-Karnamritam

Authors: Raghavendra G.S., Srishan Thirumalai, Hari Ravikumar

Who are you, boy?

Bala’s younger brother!

Alright, but what are you doing here?

Oh! I thought it was my home!

That’s fine, but

Why might your hand

be inside my pot of butter?

O Mother!

I was looking for

a lost calf

Please don’t me upset!

May this quick-footed response of Krishna

to the noble gopikā, sustain us!1

kastvaṃ bāla balānujaḥ kimiha te manmandiraśaṃkayā

yuktaṃ tannavanīta-pātra-vivare hastaṃ kimarthaṃ nyaseḥ .

mātaḥ kañcana vatsakaṃ mṛgayituṃ mā gā viṣādaṃ kṣaṇād

ityevaṃ varavallavī-prati vacaḥ kṛṣṇasya puṣṇātu naḥ ..

कस्त्वं बाल बलानुजः किमिह ते मन्मन्दिरशड़्कंया

युक्तं तन्नवनीत-पात्र-विवरे हस्तं किमर्थं न्यसेः ।

मातः कञ्चन वत्सकं मृगयितुं मा गा विषादं क्षणाद्

इत्येवं वरवल्लवी-प्रति वचः कृष्णस्य पुष्णातु नः ॥

1 From the chapter called Charya-amritam, verse 2.82.

This joyous description of Krishna’s mischief makes no sense unless read with the eye of indulgence and a familiarity with the Krishna meme as it has evolved over centuries in India.

The poetry above and the Sanskrit verse that it is based on is bound to bring a big smile to those who are familiar with Krishna stories which form a huge corpus within the larger world of the unique genre called Bhakti literature.

If you are unfamiliar with this genre, Bhakti literature is unique to India. At its very core, the word bhakti implies love of God (aka Bhagavan2 in all Indian languages) and the bhaktas (those endowed with bhakti) have enriched the Bhakti literature genre for several millennia through original poetry, recreations of popular epics such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Shrimad Bhagavatam, Shiva Purana, Skanda Purana and many others. Bhakti literature has flourished in every language in almost every small village and town of this great land of Bharat. To the observer, bhakti, or the all-consuming love of the bhakta for God, may seem odd or even manic but the sweetness of the bhakta saint’s message is transforming to all who read or listen to it with an open mind.

Lilashuka’s Sri-Krishna-Karnamritam is a poetic gem in this genre and the authors of this book have done an outstanding job in making it accessible to a larger audience beyond lovers of Sanskrit. The knowledge of Sanskrit is not essential to read and love this book although the knowledge of Sanskrit and Sanskrit poetry will certainly enhance the enjoyment.

This book makes the reader greedy. This book triggers the greed experienced by those who glorify Bhagavān and those who revel in listening to such glories.

The three authors, Raghavendra G.S., Srishan Thirumalai and Hari Ravikumar have delved into Lilashuka’s joy-filled ode to Krishna and his life. They have carefully selected what they consider are the choicest of the verses.

The poetry is intermingled with the narrative style of a katha, the traditional Indian form that very loosely approximates the balladeers of Britain and Europe. Typically, the traditional katha would have been narrated in a public area like the large outside concourses of temples. However, here the authors chose a cosy setting of a discussion between a travelling Pauranika with the emperor of Vijayanagara Shri Krishna-Deva-Raya3 and his queen.

2 The word Bhagavan will be used in place of the usual English word God because in Sanskrit the word implies so much more. Bhagavan implies a supreme being who is endowed with absolute measures of wealth, dharma, fame, skill, detachment and unfettered freedom.

3 Krishna-Deva-Raya’s life and bio.

The result is a thoroughly enjoyable book that reveals the beauty of a classic Bhakti text.

The poet, Lilashuka, is immersed in Krishna bhakti in familiar ways. He delights in describing Krishna’s childhood antics and reimagines Krishna’s stories in Gokul and Vrindavan. If you think you know Krishna’s life and story, wait till you see the twists the poet brings to the tale.

Krishna is a divine child who loves to steal butter from the homes of the Gopis, the cowherd women in Gokul and Vrindavan. Here is how Lilashuka paints the picture of Yashoda feeding Krishna butter. Their home is that of a wealthy family who own hordes of cows.

Krishna is dancing gleefully

and so is his reflection in the bejewelled pillar.

A sight to behold indeed!

The doe-eyed one [Yashoda] watches the dance

And for a moment is deceived

(She thinks there are two Krishnas)

She takes the ball of butter in her hand

And divides it

To offer them both!4

नृत्यन्तमत्यन्त विलोकनीयं

कृष्णं मणिस्तम्भगतं मृगाक्षी ।

निरीक्ष्य साक्षादिव कृष्णमग्रे

द्विधा वितेने नवनीतमेकम् ॥

Take the famous tale of mother tying Krishna out of frustration at the repeated complaints of the boy stealing butter. In avatara-amritam, the bard reveals how deftly he switches from the mother-child viewpoint to the creator-creation viewpoint. To understand this verse, keep in mind the baby Krishna is an avatara of the creator of this universe. In the Hindu view of cosmos, when we cause pain to God, since He is creation, all creatures feel the pain.

4 From the chapter titled Vātsalya-amritam, verse 2.67.

Unable to bear Krishna’s antics,

the gopikās of Gokula

often complained to Yashoda.

One day, at her wits-end

she tied that butter-thief

(to a pounding stone)

using a strong churning rope.

The rope fastened round his waist

ended up causing

vociferous outburst from

the dwellers of the three worlds

residing in his belly!5

ghoṣa praghoṣa śamanāya matho guṇena

madhye babandha jananī navanīta-coram.

tadbandhanaṃ tri-jagatāmudarāśrayāṇām-

ākrośa-kāraṇamaho nitaraṃ babhūva ..

घोष प्रघोष शमनाय मथो गुणेन

मध्ये बबन्ध जननी नवनीत-चोरम् ।

तद्बन्धनं त्रि-जगतामुदराश्रयाणाम्-

आक्रोश-कारणमहो नितरं बभूव ।।

Dreams play an important role in Indian literature. Here, again in avatara-amritam, the poet imagines Krishna dreaming about his role as Mahavishnu, the one to whom all Gods pay tributes. Poor Yashoda has no clue as to what’s going on.

O Shambho!

Welcome, sit here!

Padmāsana, (Brahma),

Here, to the left.

Kraunchāre, (Skanda or Kartikeya),

Hope all is well?

Surapate (Indra),

Hope you’re doing fine!

O Vittesha (Kubera),

Long-time no see!

Thus spoke Kaitabha-vanquisher (Krishna)

5 In the chapter titled avatara-amritam, verse 2.23.

In his sleep!

And upon listening to words,

Yashoda said,

“What all do you blabber, my child!”

Then she exclaimed,

“Dhū! Dhū!

“Away with you, evil spirits!”6

śambho svāgatamāsyatāmita ito vāmena padmāsana

krauñcāre kuśalaṃ sukhaṃ surapate vitteśa no dṛśyase .

itthaṃ svapnagatasya kaiṭabhajita:śrutvā yaśodā giraḥ

kiṃ kiṃ bālaka jalpasīti racitaṃ dhū dhū kṛtaṃ pātu naḥ ..

शम्भो स्वागतमास्यतामित इतो वामेन पद्मासन

क्रौञ्चारे कुशलं सुखं सुरपते वित्तेश नो दृश्यसे ।

इत्थं स्वप्नगतस्य कैटभजित:श्रुत्वा यशोदा गिरः

किं किं बालक जल्पसीति रचितं धू धू कृतं पातु नः ॥

For every verse selected, the narrator, the king and queen (who are themselves scholarly rasikas [aesthetes]) briefly discuss the high points of the verse and the themes that the poet plays with. The authors have been consistent in providing unique viewpoints to the two royal participants.

I was a little surprised by the unorthodox transliteration used. I felt it didn’t work for me maybe because I am used to more frequently used ISO schema for transliterating Sanskrit. But that is a minor quibble about a veritable banquet of Bhakti poetry.

When one talks about the old literary figures in India, someone inevitably asks which era the poet lived in and what was his profession. About the former, it is not entirely clear but as for his vocation provides a clue – he probably earned his keep writing odes to the kind of the land.

Lilashuka was said to be a bard at the court of the king of his land. He expresses regret at deploying the power of words and the arts in serving mere mortals and seeks redemption. In his mind, this “Nectar to the Ears” is his attempt at expiation for his “sin” driven by the need to make a living.

6 In the chapter titled avatara-amritam, verse 2.59.

O mother,

there’s nothing more inappropriate

than my having made you dance

before villainous people,

suppressing all qualms,

merely to fill this stomach!

Please forgive this lapse, O Vāni7 ,

for you are benevolent by nature.

As prayashchitta8,

I shall extol the deeds of Vishnu

in the form of a cowherd-boy!9

mātarnātaḥ paramanucitaṃ yatkhalānāṃ purastād

astāśaṃka jaṭharapiṭharīpūrtaye nartitāsi .

tatkṣantavyaṃ sahajasarale vatsale vāṇi kuryāṃ

prāyaścittaṃ guṇagaṇanayā gopaveṣasya viṣṇoḥ .. 2.4 ..

मातर्नातः परमनुचितं यत्खलानां पुरस्ताद्

अस्ताशड़्कं जठरपिठरीपूर्तये नर्तितासि ।

तत्क्षन्तव्यं सहजसरले वत्सले वाणि कुर्यां

प्रायश्चित्तं गुणगणनया गोपववेषस्य विष्णोः ॥ २.४ ॥

For me this book represents a delightful, yet important contribution to bringing bhakti literature to readers everywhere.

In all this, I have not addressed the numerous poetic meters through which Lilashuka manifests his artistry. Firstly, I am myself not very knowledgeable about Sanskrit meters and secondly, I sincerely hope that very shortly the authors collaborate with an artist to produce at least an audio or multi-media version of this brilliant work.

7 An epithet of Sarasvati, the Goddess of all arts and learning.

8 Expiation or penance

9 In the chapter titled Karna-amritam, verse 2.4